Geodesics

The Straightest Lines in Curved Space and Time

Traveler, there is no path.

Paths are made by walking.Antonio Machado

One of the most important duties of Physics is to predict how things move. Newton wrote his First Law of Motion, saying that things move in straight lines, unless some force is pushing or pulling on them. In curved space, it's hard to tell just what a straight line is. If the curvature is fairly smooth, however, there is a trick.

Many people through history have thought that the Earth must be flat. Some still do! Of course, most of us accept that the Earth is one huge sphere (approximately). The flat Earth idea worked reasonably well, though, because it is nearly flat on a human scale. And there's the trick. Looking closely enough, a curved space will look flat, so we still know what a straight line is. We can move just a little bit along a straight line, then stop. Look again, and we have another little straight line to follow in the same direction. Taking many of these tiny steps builds up into one long line. This type of line is called a geodesic, and it's the closest thing to a straight line we can find in warped space.

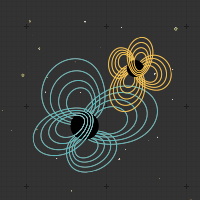

For example, imagine going between two points on the Earth's surface. Suppose you want to go from New York City to Rome, Italy, and you can't tunnel. The quickest way to go is to fly around the surface of the Earth. These two cities are at nearly the same latitude. However, when the plane takes off from New York, it won't be headed due East. If the pilot chose this route, the plane would end up in Africa, or would have to be turning left for the whole trip. (See for yourself with a little toy car and a globe.) Instead, the pilot heads a little North of East — by 33 degrees, if we ignore winds. This way, the plane can go in a straight line, and end up in Rome. That is, the plane can follow a geodesic to make the flying easier.

Now we can visualize the trip. The whole time, the plane can just keep flying straight and level. The pilot doesn't need to be turning either left or right, but will end up in Rome nonetheless. It turns out that this is also the fastest route; a "straight line" is still the shortest distance between two points, even if it's a straight line that curves. This is, basically, the path that flights from New York to Rome actually follow.

We've just described geodesics in space; the plane's path follows a geodesic along the two-dimensional surface of the Earth. Geodesics can also be paths through time. In our charts of the movements of the astronauts above, each of the lines was a geodesic — straight lines from one point in spacetime to another. But we were imagining our astronauts to be in a nice, flat spacetime. Interesting things happen when we take our geodesics through warped spacetime.

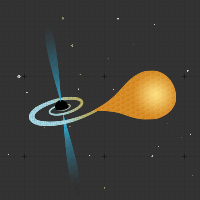

Just as the geodesic "straight line" from New York to Rome looks curved to us, the geodesic of an astronaut moving through warped spacetime would look curved, too. We can see what this looks like. For a particular type of spacetime curvature, we get the chart shown to the right.

This looks like an acceleration. In his General Theory of Relativity, Einstein kept Newton's First Law of Motion — objects still move along straight lines (geodesics) unless something is pushing or pulling on them. In Newton's world, this meant that the astronaut above would have to be pulled by some force, like gravity. In Einstein's world, it may just happen that spacetime is curved, so the astronaut only appears to accelerate, while she is simply following a geodesic. Einstein accomplished that most important duty of Physics — predicting how objects move — by understanding how and why spacetime warps.