A Totally New Kind of Observatory

Measuring the Tiniest of Fluctuations in Spacetime

From Galileo's first telescope to today's most sensitive neutrino telescopes, astronomers have been developing new eyes with which to see the night sky, allowing them to discover new worlds while better understanding our own. Now, for the first time, astronomers are creating new ears with which to hear the Universe around us.

The sounds we hear in our ears are carried through the air around us. Anything giving off sound gives the air more pressure, then less pressure. These changes in pressure travel as waves, until they reach our ears and push on our eardrums. The waves don't move our heads very much, but they move our eardrums, which allows the delicate mechanisms in our ears to pick up these movements relative to our heads.

Since sound needs air (or some other matter) to compress, sound can't travel through empty space. Gravitational waves, on the other hand, don't need air to travel; they just need spacetime. They travel across the Universe from its deepest reaches, never stopping or slowing down — regardless of the presence or absence of air. Nonetheless, they have a similar effect on our ears. As a gravitational wave passes through your head, the positions of your eardrums change relative to the position of your head. Again, the delicate mechanisms in your ears would pick up these movements, and your brain would turn them into sounds. But why aren't we kept up at night with the noise from black holes everywhere falling into each other?

It turns out that, by the time gravitational waves from these distant sources reach us, they are incredibly quiet. The smallest sound that a human with good ears can hear is roughly the sound of a mosquito buzzing 10 feet away. Gravitational waves reaching the Earth are typically another three trillion times quieter than this. To put it another way, consider the sound of an atomic blast 20 feet away. That sound (though you wouldn't be around to hear it if you were there) is as much louder than the mosquito as gravitational waves are quieter.

So how can physicists hope to hear such amazingly small sounds? There are three main tricks: Use a really sensitive microphone, make that microphone enormous, and keep everything really quiet.

| Decibel Level | Eardrum Movement | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 250 | 100 inches | Atomic bomb blast 20 feet away |

| 150 | 10-3 inches | Loudest rock concert |

| 130 | 10-4 inches | Threshold of pain |

| 110 | 10-5 inches | Symphony orchestra |

| 90 | 10-6 inches | Jackhammer from 6 feet |

| 70 | 10-7 inches | Vacuum cleaner from 3 feet |

| 50 | 10-8 inches | Office or restaurant inside |

| 30 | 10-9 inches | Residential area at night |

| 10 | 10-10 inches | Rustling of leaves in soft breeze |

| 0 | 3×10-11 inches | Threshold of human hearing |

| -250 | 10-23 inches | The typical sound of the Universe in gravitational waves, as measured on Earth |

Basic Interferometers

Scientists are recycling an old idea — one which was crucial in the earliest stages of Relativity theory — to try to detect gravitational waves. The Michelson interferometer is a very sensitive instrument which originally showed that the speed of light is the same, no matter which way it goes. Now, that same sensitivity is being used to detect the tiny fluctuations due to gravitational waves. The detector relies on interference between light waves. A wave is a disturbance which brings some “medium” higher or lower than that medium would be without any waves. For example, a wave in water has the water as its medium, and it carries the water higher or lower than the undisturbed water. Now, it might happen that two different waves are traveling along the medium and meet. They might try to move the medium in different ways. When one wave tries to bring the medium higher, and the other tries to bring the medium lower, they cancel each other out, and there is simply no change to the medium. This is called “destructive interference.” On the other hand, the waves may try to change the medium in the same way. In this case, they will add to each other, and disturb the medium more than either wave could manage alone. This is called “constructive interference.”

Whether the waves are interfering constructively or destructively depends on whether their peaks match up at the same place at the same time, or not. If we imagine keeping one wave in place, and shifting the other by just a little bit — half a wavelength, for instance — the waves will switch between interfering constructively and destructively. That is, they will switch between producing very large waves and producing no waves at all.

This allows us to use a very clever trick to measure distances very precisely. It turns out that half a wavelength of light is roughly one one-hundred-thousandth (1/100,000) of an inch. By “moving” a light wave by just this tiny distance, we could see its interference change from completely constructive to completely destructive. A light wave can be moved by bouncing it off of a mirror, and moving the mirror. Thus, we could set it up so that light bounces off a mirror and interferes with another light wave. Moving the mirror by these tiny distances we would see the total light wave would go from light to dark. One clever instrument to accomplish this is an interferometer.

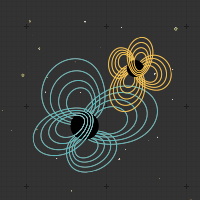

The interferometer works by splitting a single laser beam into two parts, sending them along different paths, and then recombining the two parts, allowing them to interfere with each other. In the picture above, the two separate paths of the laser are shown colored blue and red, just for illustration. If the distance along the two paths is exactly the same, the two halves of the laser beam will interfere constructively, giving the original beam back; if the distance along the paths is slightly different, the two halves can interfere destructively. Clearly, if we change the position of one of the mirrors by just half a wavelength, the two paths will have different lengths, and the final beam at the detector will change between constructive and destructive interference. With sensitive electronics, it is possible to detect very slight dimming of the final laser beam, so a shift of only a small fraction of a wavelength is noticeable. This is a very sensitive instrument.

Recall the effect of a gravitational wave. If the wave were passing directly through the interferometer from above, we can see that the path of one beam would get shorter as the other got longer, and vice versa. This is exactly the type of motion that would change the final beam between destructive and constructive interference. This trick is fundamental to the design of gravitational-wave detectors now being designed and built.

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory

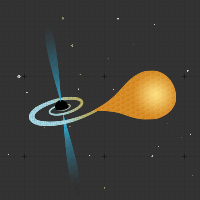

An American collaboration of physicists have built and begun operating the largest and most sensitive gravitational-wave detector that currently exists: the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory, or LIGO for short. There are actually two totally separate LIGOs, one in Louisiana and one in Washington state. The two separate instruments are necessary because a possible signal found by one might just be noise that happens to look like a gravitational wave, but if that signal is also found by the other instrument, it's almost certainly real.

Each arm of the interferometers in LIGO is four kilometers long (almost two and a half miles long). Why so big? Well, remember that the amplitude, of a gravitational wave is the percentage of stretch or squeeze by which it distorts objects. Now, we can't change the amplitude of the waves we detect, because they're just given to us by Nature. If each interferometer arm were just one meter long, a gravitational wave of amplitude 10-23 would change the distance each half of the laser beam goes by just 10-23 meters. On the other hand, if each arm were one kilometer long, the same gravitational wave would change the distance each half of the beam goes by 10-20 meters. This is still tiny, but is much better. So, we see that the longer the arms of the interferometer are, the easier it will be to detect gravitational waves.

Each arm of the interferometers in LIGO is four kilometers long (almost two and a half miles long). Why so big? Well, remember that the amplitude, of a gravitational wave is the percentage of stretch or squeeze by which it distorts objects. Now, we can't change the amplitude of the waves we detect, because they're just given to us by Nature. If each interferometer arm were just one meter long, a gravitational wave of amplitude 10-23 would change the distance each half of the laser beam goes by just 10-23 meters. On the other hand, if each arm were one kilometer long, the same gravitational wave would change the distance each half of the beam goes by 10-20 meters. This is still tiny, but is much better. So, we see that the longer the arms of the interferometer are, the easier it will be to detect gravitational waves.

In fact, LIGO uses another trick to basically make its arms even longer than four kilometers: it bounces the laser back and forth hundreds of times. This is like folding up hundreds of interferometer arms into the concrete tubes of the instrument. But this trick can only get us so far. It's just not practical to make the arms too long, or to bounce the laser beams back and forth too many times; there's simply too much noise — earthquakes on the other side of the planet, passing trains, falling trees, even waves crashing on the shore hundreds of miles away. Instead, scientists are proposing to make another interferometer, which will be immune to some of the biggest problems LIGO faces.

The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna

Removed from all the noise of earth and given all the room it needs, an interferometer in space will have be able to detect gravitational waves far more sensitively than one on earth. Scientists at NASA and ESA (the European Space Agency) are designing a system they call the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna — LISA. It will consist of three separate spacecraft, separated by 5 million kilometers! The three spacecraft, basically, form the three important ends of an interferometer.

Removed from all the noise of earth and given all the room it needs, an interferometer in space will have be able to detect gravitational waves far more sensitively than one on earth. Scientists at NASA and ESA (the European Space Agency) are designing a system they call the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna — LISA. It will consist of three separate spacecraft, separated by 5 million kilometers! The three spacecraft, basically, form the three important ends of an interferometer.

Because of the enormous distances, the laser beam won't be able to bounce back and forth between the spacecraft — it would get too dim. Instead, the beam sent from one will be detected by a second spacecraft, and delicate electronics will make a laser on that second craft perfectly match the incoming beam, and shoot it back to the first spacecraft. Still, the basic principle is the same; LISA is just an enormous interferometric gravitational-wave detector. And in fact, because it forms a complete triangle, there will be three interferometers — each with its center in a different craft — just to make sure that a failure of one won't doom the entire project.