Extreme Mass-Ratio Inspirals

An Elegant Pas de Deux, Setting Off Waves Ringing Out Across the Cosmos

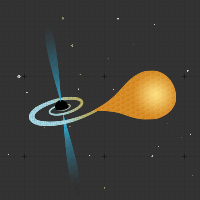

The centers of most galaxies — even our own — are believed to contain supermassive Black Holes, which contain millions of times as much mass as our Sun. Over the lifetime of such a Black Hole, lying right in the busiest part of a galaxy, it will consume millions upon millions of stars — that's how it forms. These stars will happen to pass too close to the Black Hole, and become trapped in its gravitational field. They will spin around and around, giving off gravitational waves, gradually spiraling in. This type of event gives us a particular type of compact binary, called an extreme mass-ratio inspiral (or EMRI).

The centers of most galaxies — even our own — are believed to contain supermassive Black Holes, which contain millions of times as much mass as our Sun. Over the lifetime of such a Black Hole, lying right in the busiest part of a galaxy, it will consume millions upon millions of stars — that's how it forms. These stars will happen to pass too close to the Black Hole, and become trapped in its gravitational field. They will spin around and around, giving off gravitational waves, gradually spiraling in. This type of event gives us a particular type of compact binary, called an extreme mass-ratio inspiral (or EMRI).

The beauty of an EMRI lies in its simplicity. The central black hole is so massive that it will be almost entirely unaffected by the smaller star. In a binary where the stars have nearly equal mass, on the other hand, both will be distorted in weird — and hard to calculate — ways. For an EMRI, however, the smaller star just doesn't have the pull to effect the larger one. Astrophysicists believe that they understand a lone black hole quite well. Observing an EMRI will give them a chance to test that understanding, as the gravitational waves given off by the smaller star map out spacetime near the larger one. What's more, the inspiral will take much longer than a regular compact binary inspiral, giving them more data to use for their tests.

The progressively closer encounter of two black holes

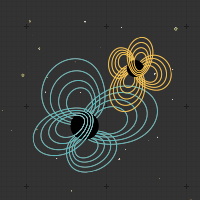

The knocking inspiral of two black holes, as their orbit draws them closer and closer

The chirping inspiral of two black holes