Movies

Watch clips of black holes colliding

Highly-precessing binary black hole run

Binary black hole system with spin of 0.91 on the large hole and 0.3 on the small hole. The mass ratio is 6:1. Colors indicate the vorticity of the apparent horizon and arrows denote the spin directions. The large spin produces significant orbital precession. Movie rendered by Robert McGehee and Alex Streicher.

Vortex-Tendex Visualization

Head-on Collision of Equal-Mass Black Holes with Transvere Spins

The spins of the black holes are transverse to the infall direction, anti-aligned and of magnitude 0.5. This simulation is descrbed in a publication Phys. Rev. D, also available at gr-qc/0907.0869.

Inspiral of Equal-Mass Black Holes with Spin Anti-Aligned to the Orbital Angular Momentum and of Magnitude 0.95

The spins have magnitude 0.95, are parallel to each other, but are anti-aligned with the orbital angular momentum. This simulation is described in a publication in Phys. Rev. D., in press. The paper can also be accessed at arXiv:1010.2777.

- The evolution of the spin function (imaginary part, χ, of the Penrose-Rindler complex curvature, κ) on the apparent horizons

- The evolution of the scalar curvature, R, on the apparent horizons

Note that aside from corrections that become important only near the time of merger, the spin function χ and scalar curvature R should agree well with -2Bnn and -2Enn, respectively, where Bnn and Enn are the horizon vorticity and tendicity, respectively.

"Extreme-Kick" Merger: Inspiral of Equal-Mass Black Holes with Spins Anti-parallel and Oriented in the Orbital Plane

The spins of the black holes are anti-parallel, oriented in the orbital plane, and are of magnitude 0.5. In this configuration, the kick of the final black hole has been observed in simulations by Campanelli et al. to depend on the phase of the binary at the time of merger; more specifically, they found that the kick depended sinusoidally upon the angle between the initial momenta of the BHs and the spins. This simulation will be detailed a future publication in progress; it is discussed in a paper submitted to Phys. Rev. Lett., available at arXiv:1012.4869.

- The evolution of Enn, the tendexes, in the apparent horizons

- The evolution of Bnn, the vortexes, in the apparent horizons

Demo: Binary Orbit & Collision, Head-on Collision

The following movie is divided into two parts, each part showing a different numerical simulation, with brief captions that describe what is being shown. Part 1: Binary black holes orbit, lose energy because of gravitational radiation, and finally collide, forming a single black hole; gravitational waveform, spacetime curvature, and orbital trajectories are shown. Part 2: Event horizon and apparent horizons for the head-on collision of two black holes.

Falling Spacetime

The upper movie shows in the upper half of the screen the orbits and the apparent horizons of the two holes, in the coordinate system used in the computation. The bottom half of the screen shows the spacetime geometry in the holes' orbital plane. The depth of the surface is proportional to the scalar curvature of space. (For the two-dimensional orbital plane the full spatial curvature is determined by the scalar curvature.) The colors encode the lapse function — the slowing of the rate of flow of time. The arrows show minus the shift — which can be thought of as the velocity of flow of space. The beginning of the inspiral is shown, and then the last several orbits, the merger of the two holes, and the vibrational ringdown.

The final hole does not look pefectly spherical because the computer code that created this movie chose spatial slices with a bit of crinkliness in them at the end. This simulation lasts for 16 inspiral orbits, followed by merger and ringdown, and it achieves a cumulative phase accuracy for the emitted gravitational waves of about 0.02 radians (out of roughly 200 radians, i.e. a fractional phase error of 1 part in 10,000).

Tehnical details of the simulation on which this movie is based can be found in a paper by the Caltech-Cornell group. Note that slightly different data is used in that paper; the spatial slices are chosen without the “crinkles”.

Gravitational Waves From a Pair of Black Holes From Large Distance

On the right side, this movie shows the gravitational waves emitted by a pair of black holes from large distance. The black holes themselves are in the center of the ball, too small to be seen. Toward the left of the ball showing gravitational waves, there is a little grey dot. The red line on the left side shows the gravitational wave strength which would be observed if a gravitational wave detector would have been at that place. If you look carefully, you'll notice that gravitational waves are emitted in all directions, but that the waves are strongest in the "upward direction", which is normal to the orbital plane of the holes. This is an older movie, which stops just before the black holes collide.

Gravitational Waves From a Pair of Black Holes Orbiting Each Other

This movie shows a pair of black holes orbiting each other, giving off gravitational waves. The movie begins with a close-up view of the holes. We zoom out, to show some of the surrounding spacetime. As the holes go around, they give off waves. After an initial burst of "junk radiation" (unrealistic artifacts of the simulation), the animation speeds up – just so it doesn't take so long – and we see nice spiral-shaped waves. Gradually, the black holes begin to orbit faster and faster. As they do, the waves become more and more intense. If you watch carefully, you can see the circles on the top and sides oscillating, just as you would expect from a passing gravitational wave.

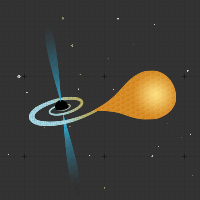

Precessing Black Hole-Neutron Star Merger

This movie shows the merger of a black hole-neutron star binary in which the spin of the black hole is not aligned with the total angular momentum of the system, thus causing the orbital plane to precess. The black hole is 3 times more massive than the neutron star, and has a spin a=0.5 at an initial inclination of 80 degrees with respect to the orbital angular momentum of the binary. The main frame shows the evolution of the system from slightly above the initial equatorial plane, with the color scale giving the density of matter within the star, while the smaller panel shows the same system viewed from an "edge-on" position (i.e.: as seen by an observer located in the initial equatorial plane).

The binary goes through about 2 orbits, during which the separation between the compact objects drops from 60km to 30km. Then, tidal forces disrupt the neutron star. Most of the matter (~97%) is rapidly accreted by the black hole, while the rest forms a long tidal tail which eventually settles into an accretion disk. The relative precession of the star, tail and disk is clearly visible in the edge-on view. Towards the end of the simulation, the spin of the black hole and the angular momentum of the disk are misaligned by about 20 degrees, which will cause the precession of the disk over longer timescales.

Merging Event Horizons

This movie shows the event horizons of two black holes merging into a single black hole. The holes have a 2:1 mass ratio, with spins of approximately 0.4 in random directions. The merger simulation has been published in gr-qc/0909.3557, by Bela Szilagyi, Lee Lindblom and Mark Scheel at Caltech. The event horizon tracking was performed by Michael Cohen at Caltech.